Could this sheet be unique?

Stanley Gibbons’ July 26-28 sale features a rare Queen Victoria 5s Specimen sheet—but how rare? And what significance did it hold for its former owner?

[Post-sale update: Somewhat to my surprise, the sheet was hammered down for slightly less than its pre-sale estimate: £14,000, coming to £16,800 with the buyer’s premium. Realizations in PDF form for the three days are here (day 1), here (day 2) and here (day 3). A blank next to the lot number indicates an item did not sell; contact SG directly if you are interested in buying such items post-sale.]

[Sunday update: I have incorporated some additional information and comments from Karl Louis, Scott Trepel and Tom Droege, below, in italics]

The printed catalog for the next Stanley Gibbons auction, whose 1,933 lots will be offered over three days from July 26 to 28, landed with a thud in my office last week. It weighs in at 328 pages, but there’s no need to even open it: the heart stopper is right there on the back cover.

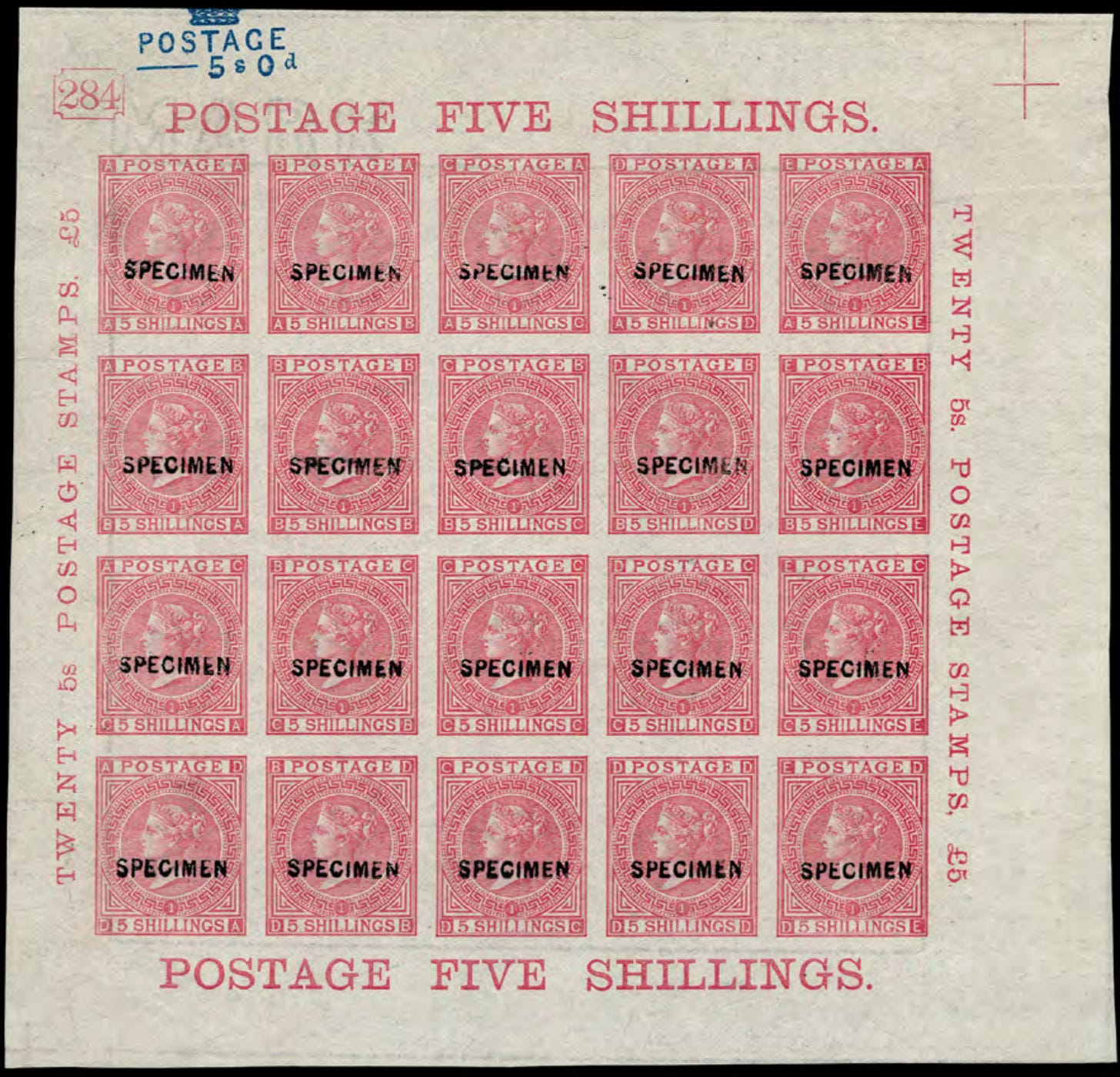

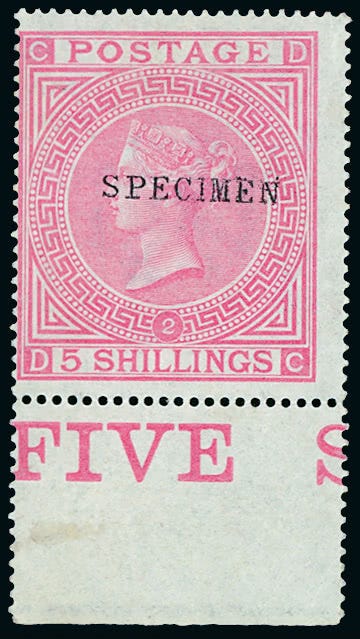

Lot 1426 is a full mint sheet of 20 of Great Britain’s 1867-74 Queen Victoria 5-shilling rose, Plate 2, with all the marginal inscriptions and a good deal of original gum on the back. Each stamp is hand-canceled with a small “Specimen” overprint. Aside from a few trivial creases, marginal thumbprints and some minor separation of the perfs, it’s a stunner. Mint stamps of early Queen Victoria are rare. Mint multiples are even rarer. Full mint sheets, even when covered in “Specimen” handstamps, are the stuff of dreams.

Now, I’ve looked at a lot of classic G.B. items and browsed a lot of catalogs from famous-name sales of the past. When you come across an item as big and beautiful as this, you tend to remember it. And I couldn’t for the life of me remember seeing this sheet anyplace before.

I reached out to Gibbons and they first pointed me towards the great “Verus” collection, which they broke up and sold in 2015 and which included a specimen sheet of the 5s rose. But that sheet, when I looked it up, was an imperforate sheet of Plate 1, not Plate 2. (The plate number appears in a tiny circle just below the bust of Victoria in the design of each stamp.)

I nudged them again, and Tom Hazell, the head of auctions at S.G., swiftly replied:

It was purchased in August 1960 from Wingfield by the Grandfather of the current vendor… The Grandfather passed away in the 70s and it was inherited by his son who also passed away and it was subsequently left to his grandson who has now put it up for auction – so it has been in the same family for 62 years.

That would explain why I didn’t recall seeing it before. It’s been in hiding since Harold Macmillan was Prime Minister and Keith Richards could barely play guitar!

The venerable stamp firm of H.E. Wingfield, old-timers may remember, used to be located in the Strand next door to Stanley Gibbons. The two firms merged in 1962 and A.L. “Mick” Michael RDP, the head of Wingfield, became managing director and later chairman of Gibbons.

This sheet is described as an “extremely rare multiple,” which may, in fact, be a bit of an understatement. Auction firms typically hedge their bets in such matters, and you can’t blame them. But I believe there are unlikely to be more than one or two other such sheets in existence, and this may very well be the only one.

Let me explain why I think so. This requires a short digression to take a look at the history of the 5s rose and its specimens.

Britain’s first high-value stamps were issued in 1867, after years of clamoring from inside and out the post office for something bigger than a shilling. The new 5s came at the same time as the 2s blue and the surface-printed 10d. There was little need from postal customers for a denomination that large, but because internal accounts in provincial offices were balanced by means of stamps, the bureaucrats were getting tired of licking a lot of small stamps whenever they needed to close their books. To them, the 5s rose would have been a godsend. It would have also seen some use on parcels (and later on, of course, on telegraphs).

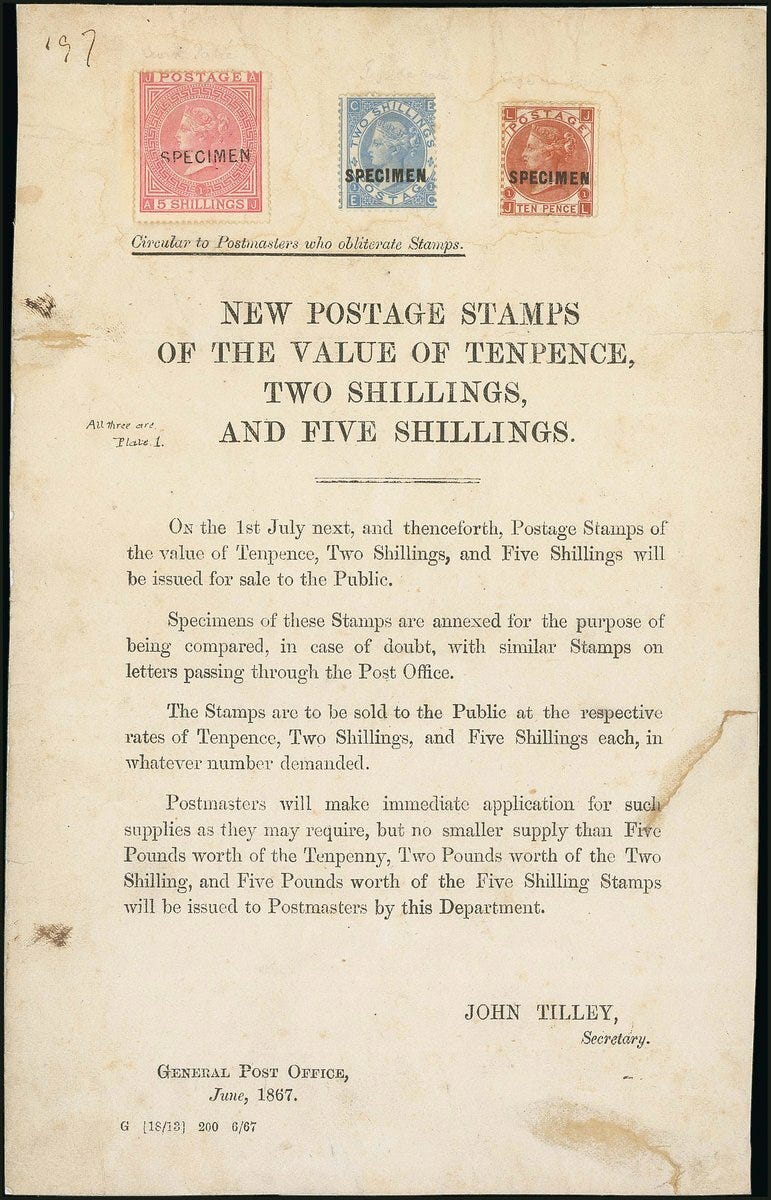

A “Circular to Postmasters who obliterate Stamps” of June, 1867 announced the three new stamps, available to the public “in whatever number demanded.” An example of this notice from Spink’s recent Klempka Family Collection sale, where it brought £2,700 before buyer’s premium, is shown here:

By way of illustration, the notice bears a sample of each stamp stuck to the top of the sheet, overprinted “Specimen”. All three stamps are from Plate 1 of their respective issues (some useful idiot, sometime in the past, decided to write this rather obvious fact on the sheet in pen. Note to readers—don’t do this!)

In the days before color reproduction was easy, attaching a specimen was the most practical way to show postmasters what the new stamps looked like. Rather than gifting them the 7 shillings and 10 pence, however, the stamps were marked “Specimen” so they could not be removed and used.

Hundred of copies of this postal notice were distributed up and down the British Isles, though only a few have survived intact. Understandably, a fair number of 5s specimen stamps from Plate 1 were produced for this purpose; it was the primary raison d’être for stamps with “Specimen” overprints during the 1860s. Many of these singles, long since soaked off their notices, reside in collections today.

Such a notice, dubbed a “birth certificate” by philatelists, advised that postmasters were to order a minimum of one sheet (£5 worth) of the 5s. One post-office sheet, that is: the stamps were actually printed in sheets of 80, divided like a window sash into four panes of 20 (each with four rows of five stamps).

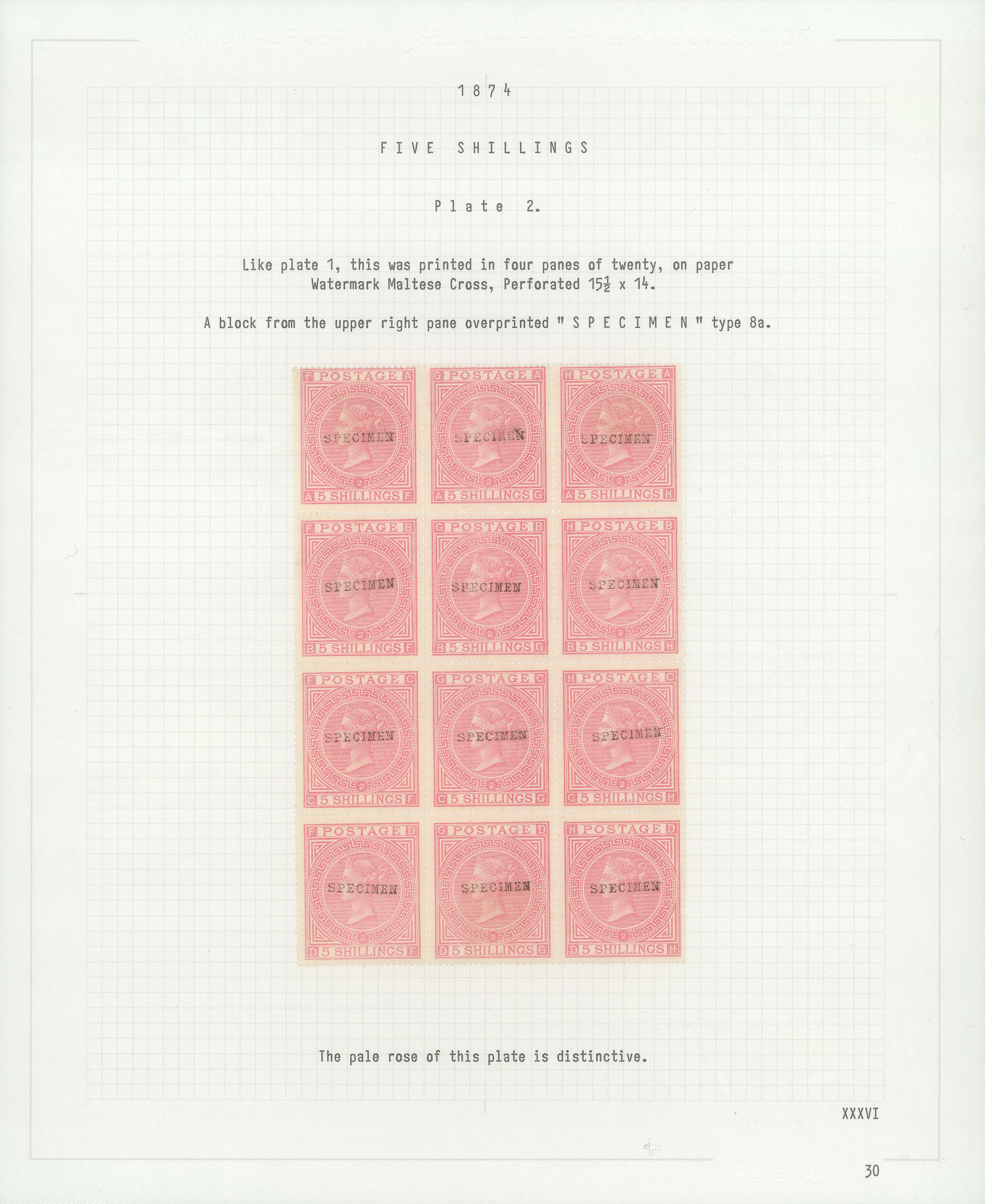

The only surviving full press sheets of the 5s are in London’s Postal Museum, which has graciously scanned them and put them online for study. Here is the one for Plate 2, made at the time the plate was registered and now rather severely mutilated, for better or for worse (depending on your point of view as a collector—many of the missing stamps are in private collections):

Note that the upper left pane, matching the sheet offered by Gibbons, remains miraculously intact.

Each stamp has letters in the four corners of the design indicating its position in the sheet: AA at upper left, followed by AB, AC etc. all the way across to AJ; then on the second row BA, BB and so on, down to HJ in the bottom right corner. (The letters in the lower corners of the stamp are the relevant ones; the letters in the upper corners are just the same pair, reversed.) The Plate 2 pane now offered by Gibbons is lettered from AA to DE.

In the upper left margin is a boxed numeral, 294: this is known as the current number, and was a cumulative count of all the stamp plates prepared by De La Rue, the firm that printed virtually all of Great Britain’s 19th century letterpress postage and revenue stamps. The current number was repeated in the lower right margin. In the upper right and lower left corners (missing from the imprimatur) was the plate number, 2, specific to the 5s issue. (The earlier Plate 1, as we’ll soon see, bore the current number 284.)

Besides the single Plate 1 specimens originating from postal notices, a small number of multiples and full sheets with specimen overprints also survive. Not all of the surviving sheets are the same, however.

There are two in the Postal Museum, where they are part of the legendary Reginald M. Phillips collection. Both are Plate 1; one is perforated, and one imperf. Phillips’ write-up indicates that the perforated sheet has type 2 of the Specimen overprint and the imperf type 6, which should be a slightly smaller and bolder version (see below).

Either old Reg was mistaken, however, or the classification has changed since he made his pages: both sheets have type 6 overprints, albeit of slightly different strengths of impression. [Update: Scott Trepel observes that the specimen overprints on this sheet are remarkably regular in their placement, as if they had been printed from a single, 20-stamp forme. I’m curious to hear others’ opinions on this.]

Here’s part of the illustration of the overprints in the Gibbons QV catalog. As you can see, some of them are hard to tell apart. Phillips refers elsewhere to a type 8a, which no longer exists:

The perforated Phillips sheet may be a leftover from the preparation of the postal notices, as the 5s on the Klempka “birth certificate” also shows a type 6 overprint. The imperf Plate 1 specimen sheet from the “Verus” collection, mentioned earlier, is a close match to the imperf Phillips sheet. Note the current number, 284:

The other respect in which the two Phillips sheets of Plate 1 differ is their shade. The perforated sheet is paler, and Phillips noted “the pink shade is typical of the earliest printing.”

The two imperf sheets—both Phillips and Verus—are darker, and Phillips noted that “the deep rose carmine shade was one printed about 1870,” as part of a series of such sheets. Perhaps, therefore, these were made for an exhibition, either the Paris one of 1867 or one of the London ones in 1871-74.

What other purposes, besides postal notices and exhibitions, were specimen stamps prepared for? Sources can be vague, but there was an albeit tiny need for archival examples and samples for future reference, such as when negotiating with printers over the desired hue of ink. In such cases, it is likely that just a single sheet or even a part sheet would have been all that was produced, and it would not have required perforating.

Plate 2, though probably manufactured around the same time as Plate 1 (as hinted by the relative proximity of their current numbers, 284 and 294) was not put to press until seven years later, in 1874. By that time, the type of specimen overprint had been changed, and indeed the Plate 2 specimen sheet now offered by Gibbons has a type 9 overprint (a few type 8 examples are also recorded).

Why were specimen overprints made of Plate 2, if not for distribution to postmasters or display at a show? Presumably the bureaucracy had its reasons. But the paucity of examples indicates that the number made was very small.

The catalog description for lot 1426 notes that even the late, great Marcus Samuel had only a block of four in his legendary collection of Specimen overprints.

Samuel, you will recall, literally wrote the book, Specimen Stamps and Stationery of Great Britain (1980; together with Alan Huggins—Samuel did the adhesives, Huggins the stationery). The G.B. Philatelic Society, which is still offering the book at £40 (members £36), calls it “still the standard work on the subject.”

How does Gibbons know Samuel had a block of four? Easy—it’s in their current stock, where you can Buy It Now for £4,500 (readers of this newsletter are reminded to ask Gibbons if there’s any price flexibility on an item of this caliber… never hurts to inquire, as long as you’re seriously interested!) It’s lettered CI to DJ, from the upper right pane:

The Phillips collection has a block of 12, lettered AF to DH, from the same pane (below). The obvious implication of this block is that even the incomparable R.M. Phillips was unable to obtain a full sheet:

I pulled up the Samuel and Phillips blocks on my screen and placed them alongside one another. Shivers—they have adjacent lettering, the centering of the two blocks matches and, when blown up, it also appears their longer and shorter perf teeth align. I would surmise that the two blocks were at one time joined. (The fact that they appear to be quite different shades onscreen is simply a result of being scanned in different times and places on different equipment operated by different people, and can be ignored.)

I have not been able to locate another full specimen sheet of Plate 2 in any firm’s online auction records of the last few years. I have found scattered singles of S.G. 127s, including one lettered BB in a Spink sale last year. As it is redundant to one of the stamps in the Lot 1426 sheet, it proves there was more than one sheet originally. It also proves at least one pane was broken up for some purpose.

A search of Grosvenor’s past sales turns up a twosome lettered BI and FI, which would have come from the upper and lower right-hand panes. Interestingly, each has a different overprint—BI is type 8 and FI is type 9:

As well as a vividly hued lower-margin single lettered DC, again redundant to the present sheet and with centering similar to Spink’s BB example above:

Though Siegel’s sale of the Bertsimas collection in 2019 was awash in G.B. Q.V. mint sheets and multiples, it too had only a single, lettered DG, of 127s:

There are two inescapable conclusions: even as a single, this is a very rare stamp. As any kind of multiple, let alone a complete sheet, it is quite likely unique.

[Update: Karl Louis, of Corinphila, very graciously checked his famous card index of historic sales for me, and sent this helpful list of what he found:

I have a record of a 5s. plate 2 “....complete full o.g. pane of twenty with full margins and inscription overprinted SPECIMEN” offered by Harmer’s of London 24. January 1955, lot 462 (very likely ex Bailey collection). Unfortunately not illustrated and no letterings given (as usual at the time for Harmer’s descriptions).

I have also records of a “....mint pane of 20 overprinted SPECIMEN but off centre” (neither mentioning letterings, nor if with sheet margins or not). This pane was offered in the Vesey collection by Harmers on 26 Nov. 1933, lot 67.

Eighteen month later, on 13-14 May 1935, this pane (not sure, but very likely) was offered again by Harmer’s as lot 336. Again mentioning “off centre,” but not if with or without sheet margins.

An off centered pane of 20 (which you probably have missed), but without sheet margins, was in the Dr. Douglas Latto collection, sold by Phillips in October 1992, lot 290. This pane has no sheet margins and is markedly off-centre, lettered EF/HJ. I believe this to be the Harmers 1933 and 1935 pane, unfortunately without any proof, despite the mention of “off-centre” in the Harmer’s descriptions.

Furthermore I have three blocks of four in different centerings, of which one CI-DJ formerly made a block of six with a pair BI-BJ.

I also have two marginal strips of three.

We can’t be sure, of course, but it is possible that some of these historic lots represent the same sheets we now have either in the Gibbons sale or the in Phillips, Samuel or “Verus” collections. Some may also have since been broken up and account for the singles that show up in more recent auction records.]

StampAuctionNetwork maintains a copious storehouse of data on past sales, which is accessible to those who sign up for the site’s Extended Features. Tom Droege, the owner of SAN, has very kindly agree to compile a census of all examples of S.G. 127s that have appeared on the site over its nearly 30-year history, and I await the results shortly. [Update: Tom has now posted a video with his search results on the SAN homepage, which you can access directly here.]

If any readers have information on sales outside of SAN, or older history, please leave a comment below and I will be happy to update this article.

I have been marveling at the present vendor’s Grandfather’s good fortune in acquiring such a rare item all those years ago. Though he remains anonymous, I’ve wondered whether he was a famous collector whose name we might recognize from his prizewinning exhibits or learned philatelic publications. I also wondered what he, personally, found significant about the block and how it fit into his collection.

Gibbons’ Tom Hazell answered that one for me:

The Grandfather collected any items which had his initials on them: AD—this went for all 1d blacks and anything else, he had £5 oranges etc., all with his initials and his purchases included this item as it too had his initials on it.

So there you have it. He wanted it because it included his initials on one stamp out of the 20.

Til next week,

Matthew

Lot 1426 is estimated at £15,000-£20,000. Bidders unable to attend the sale in person can find it on Stanley Gibbons’ web site, or via StampAuctionNetwork or Philasearch.

I'm finding these analyses of the thriving market for stamp collectors to be fascinating.