Elizabeth: a brief life in stamps

As an icon and a human being, the Queen's philatelic life dates back to 1932.

It sometimes seemed, to my generation at least, as if Queen Elizabeth II would probably live forever.

Forever is rather a long time, of course. And yet, she had been queen not just for the entirety of our own lives, but for quite a long time before that as well. It is so easy to simply assume that what is will always be.

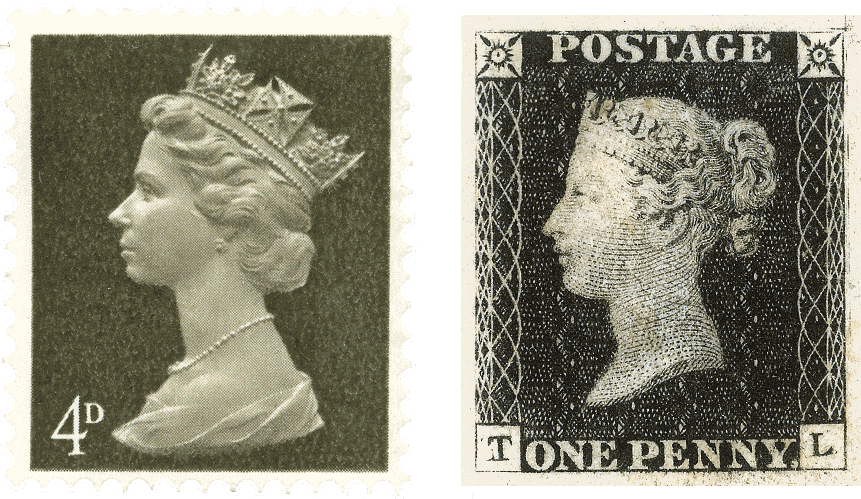

Plus, we have the stamps to prove it. There she is, frozen in time at the tender age of 40 in the effortless perfection of sculptor Arnold Machin’s 1967 bas-relief effigy that has graced billions of Great Britain’s definitive stamps for the last 55 years—in literally hundreds of different denominations and colors. Never changing, never aging a day. The stamps that were on mail I received as a boy in the 1970s—birthday cards from my Nana in London—are the stamps on the mail I receive today. This icon is impervious to the passing of time.

The Machin portrait is considered one of the great masterpieces in the history of postage-stamp design: at once contemporary and timeless, allegorical and specific. In its neoclassical simplicity, it harkens back to the design of the world’s first postage stamp, the Penny Black, which depicted Elizabeth’s great-great-grandmother, Victoria. (Elizabeth herself is said to have opted for the sepia color of the first one in the series, to reinforce the analogy to the Penny Black.)

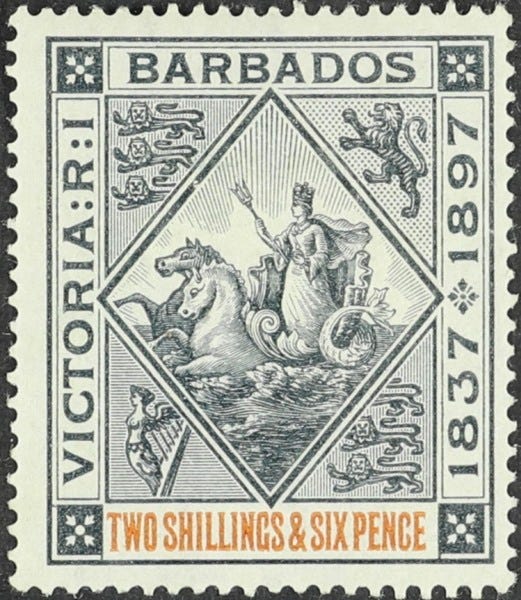

The image of a youthful queen on stamps is by now deeply embedded in the British psyche: like Elizabeth’s stamp portrait since the 1960s, Victoria’s teenage profile was unchanged throughout her reign. Having a young queen on the nation’s stamps has been the norm for 131 of the last 182 years.

There is no doubt that when Elizabeth came to the throne in 1952, the euphoria accompanying her coronation and the attendant gushing about a “new Elizabethan age” stemmed in part from the old-time Romantic symbolism of the young woman as emblematic of the state.

This type of allegory dates back to Roman times and probably even earlier. Its significance and P.R. benefits were not lost on the Victorians; they were also deftly exploited by a postwar Britain looking to come to terms with its harsh new realities and rebuild itself. The symbolism proved insufficient to stem the ebbing of empire, but one could hardly blame Elizabeth for that.

Elizabeth’s portrayal on stamps has not been solely symbolic. It has also been personal, sometimes intimately so. And unlike their more allegorical cousins—the timeless Machins—the stamps that showed us Elizabeth the real person have served to remind us that she was, after all, bound to be mortal at some point.

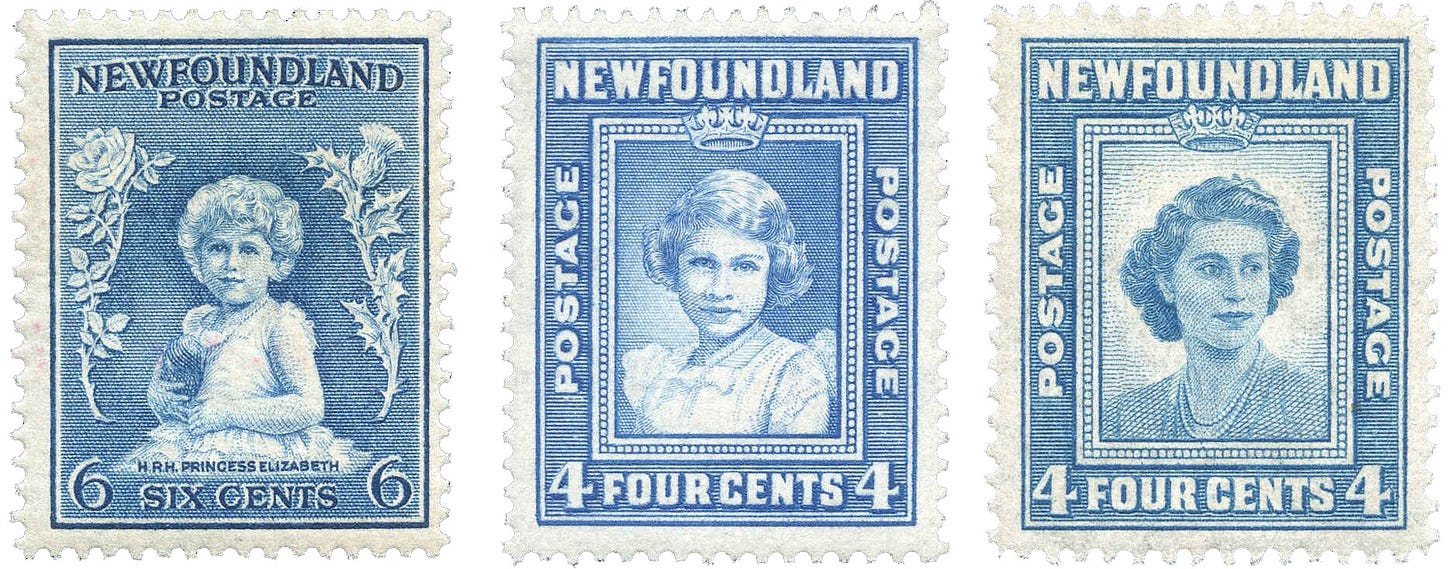

It was the rather remote and thinly populated colony of Newfoundland, on the Atlantic shores of North America, that first put Elizabeth on a stamp, in 1932. Showing royal children was something of a tradition there: an 1898 ½-cent stamp showed the future King Edward VIII as a baby, while a 1911 9-cent issue depicted the ill-fated Prince John, fifth son of King George V, who died at 14 from an epileptic seizure and never appeared on another stamp. Canada (which Newfoundland joined in 1949) put nine-year-old Elizabeth on a 1-cent stamp in 1935, marking the Silver Jubilee of her grandfather, King George V.

Other colonial realms also pictured Princess Elizabeth, whose uncle’s abdication in 1936 cemented her position as heiress apparent to the throne. New Zealand was one; several southern African countries marked visits by the royal family in 1947.

Several of these issues showed Elizabeth’s whole family: her father, King George VI, her mother, Queen Elizabeth (later known as the Queen Mother) and her younger sister Margaret as well as the future queen. A 1946 stamp from New Zealand’s set celebrating peace at the end of World War II presents a poignant family portrait.

Elizabeth, as we all know, became Queen on the death of her father in 1952. She had not, until that time, appeared on any stamps of Great Britain itself. Even her wedding to Philip in 1947 was noted with nothing more than a special postmark, a postwar economy that caused some controversy at the time.

Upon her accession, work began quickly on new stamps, and the first ones were issued the same year, based on a shoulder-length three-quarter-profile photograph of the queen by Dorothy Wilding. Garlanded by heraldic flowers, they carried on the visual tradition of her father’s stamps, albeit with a slightly more feminine touch. But the stamp that truly announced her arrival as monarch was this masterpiece by Edmund Dulac, for the 1953 coronation set:

Its bold, full-frontal portrait was unprecedented. Its elegance and symmetry perfectly synthesized the pomp and deep tradition associated with the occasion. To this day it is considered one of the best designs of Elizabeth’s entire reign.

There followed far too many stamps to show here, documenting the many milestones of the queen’s life and reign—birthdays and anniversaries galore. Royal Mail has posted this charming retrospective, showing many of the British stamps that have commemorated the Queen (not to be confused with their recent stamp issue commemorating Queen, the 70s rock band.)

One of my favorites was the set issued for the Queen’s 60th birthday, in 1986. The stamps were designed in pairs, with a set of six portraits from various stages of her life flowing across. The second image on the left, of the young teen in a jaunty cap, is particularly endearing: a picture of a human being, rather than an icon.

The Queen’s final philatelic hurrah came earlier this year, as she marked her Platinum Jubilee: 70 years on the throne. After the Silver (25), Golden (50) and Diamond (60) Jubilees, they were running out of precious materials!

The last image, chronologically, of this eight-stamp set shows Elizabeth in 2020, at age 94. In spite of her advanced years, her winning smile exudes the same aura of steadiness and self-assurance that comes through on that 1932 Newfoundland stamp.

And that, perhaps, was Elizabeth’s great genius: that for almost a century, she walked the line between human and icon, and made it seem both natural and effortless.

The Queen is dead—long live the King. And may his stamps be as wonderful as hers.

What a beautiful, beautiful column. Mom and Dad would be so proud. ❤️

Matthew,

It's truly remarkable. You're doing what only the very best specialty writers in food, in sports can do. You're making even the reader with only a casual interest in the subject want to be there and be a part of it.