Postage x Revenue

In the latest American Philatelist, I explore the intersection of stamps used for postage and revenue purposes across British Africa

If you’re one of the 26,000 members of the American Philatelic Society, you should be receiving your copy of the September issue of their magazine very shortly, if you haven’t already. (You can also read it online if you sign in at Stamps.org).

As you’ll see from the front cover, the theme this month is British Empire (on which the sun proverbially never set), with articles spanning a range of subjects. Feature subjects include the colonies (or former colonies) of Bermuda, Guyana, Sarawak and Pitcairn Island; mail sent by civilian internees in India during World War I; an important early letter from Australia to the U.S.; and a piece from yours truly on the fascinating intersection of postage and revenue stamps in some of the former British colonies in Africa.

The magazine’s editor, Susanna Mills, has put together another issue covering a range of the things people find fascinating about philately: history, geography, design, and first-hand witnesses to the pathos of the human condition. It’s not much of a stretch to say that membership in the APS ($45 annually) is worth it just for the magazine!

At the risk of being self-indulgent, I thought I’d share a little synopsis of my own article, which looks at how postage stamps and revenue stamps often overlapped during the colonial era.

In the days when government income stemmed largely from fiscal duties and legal fees, the use of stamps to account for their payment was widespread. Not only were the stamps for such revenue purposes designed, printed and distributed together with postage stamps, they were also frequently the same stamps, or very nearly so.

Exhibit A was a £1 stamp from Basutoland (nowadays called Lesotho), an enclave within South Africa that issued its own first stamps in 1933, a set of ten all featuring the same design with King George V and a crocodile. But the set, as listed in every postage stamp catalog, topped out at 10 shillings (half a pound)—the stamp on the left above. There is no mention of a £1 value like the stamp on the right.

The reason for this is found in a small detail of the design: you’ll note that in the two small ribbons near the top, the 10/- stamp is inscribed “Postage…Revenue” while the £1 says “Revenue…Revenue.” That’s not an error; that’s because £1 was far more money than one could spend posting anything in that place and time, and the stamp on the right was intended only for paying legal fees and so forth.

There were other examples of the “stealth” extension of postage stamp series with revenues, and I find them eminently collectable, despite their absence from most stamp catalogs.

A further way in which postage and revenue stamps overlapped was the repurposing of postage stamps for revenue payments, like the example shown above from the Gold Coast, which I did not include in my AP article. This example is interesting because the underlying one-penny stamp is not the same color as the one-penny stamp issued for postage: it is grey and red rather than lilac and red. The stamps were reprinted in different colors for the express purpose of being overprinted for judicial use. From a collector’s perspective, I don’t feel you can really consider your set of this issue “complete” without these revenue variants.

Among the most intriguing and beautiful examples of the crossover between postage and revenue are stamps that were designed to be used exclusively for revenue purposes, but picked up design elements familiar to us from postage stamps. In my AP article, I gave the example of the high value revenues from British Central Africa, later known as Rhodesia, which adopted the central coat of arms seen on that colony’s postage issues. But there’s another example I like even better: the series of revenue stamps issued for Griqualand West.

This is a “country” that’s so obscure many collectors—never mind the population at large—have never even heard of it. It was only in existence from 1871 until 1880, when it was absorbed into the Cape of Good Hope (now part of South Africa). For space reasons, I omitted it from my article, with some misgivings, but here it is:

Now, this is a beautiful set indeed, ranging from one penny to five pounds, and quite scarce complete in mint condition: when Spink and Son offered it at auction in London in 2015, this set went for £480, not including the buyer’s premium.

In the postage stamp catalogs, Griqualand is represented only by a few stamps of the Cape of Good Hope, overprinted with an inconspicuous ‘G’ in various random fonts—nothing very exciting. This revenue set is something else. The finely engraved portrait of Queen Victoria is by Herbert Bourne (1825-1907), and is familiar to philatelists from the postage stamps printed by Bradbury Wilkinson for Transvaal (another South African republic) and the Falkland Islands:

This is another great reason to collect revenue stamps as well as postage stamps: they can be just as beautiful, if not more so.

Finally, the ways they were used are often just as fascinating as any postal history item. I’ll leave you with one final piece, which I also did not include in my article. It’s a straight-up revenue item whose postal connection is negligible, except in the sense that the stamps were printed (as they almost always were) by the same firms that produced postage stamps, so the look-and-feel of the stamps is familiar.

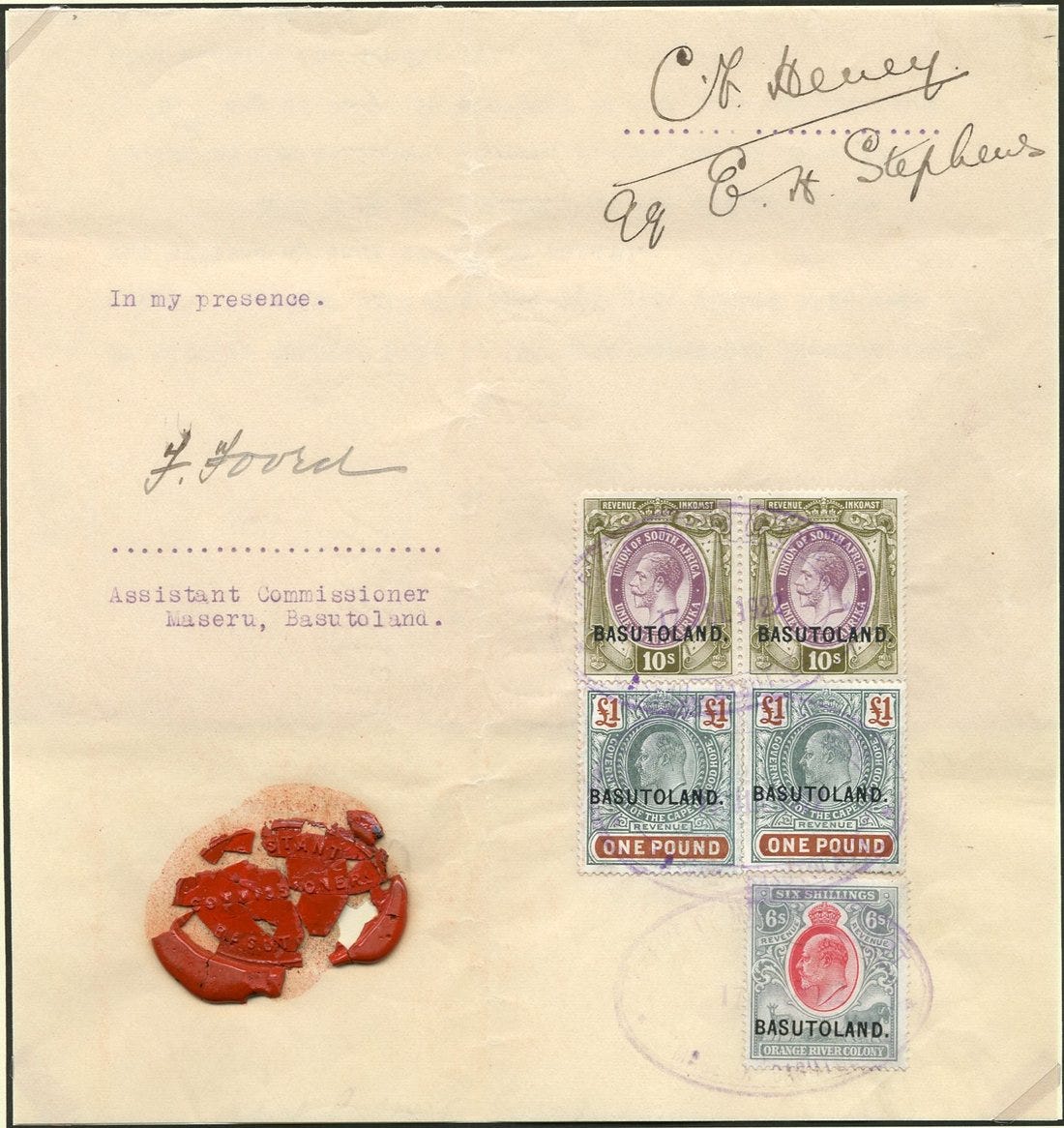

This is a page from a Basutoland mortgage bond, a typical type of revenue-stamped document. It’s dated 1922, so it predates the country’s first issue of its own stamps: prior to 1933, the country made use of stamps from neighboring colonies, which it overprinted “Basutoland.” What’s interesting here is that the underlying stamps are from three different places: the King George V 10/- pair at top was from South Africa; the £1 pair in the middle, with King Edward VII, from the Cape of Good Hope; and the 6/- stamp at the bottom from the Orange River Colony. Both of the latter two colonies were incorporated into South Africa in 1910 and their stamps eventually became obsolete. This remarkable and colorful document was sold by Spink in 2017 for £220.

I hope this quick survey has been as interesting for you as it is for me. I encourage you to explore the rich and rewarding field of revenue stamps and discover all the ways they intersect with postage stamps—and to consider joining the APS.

Til next time,