What defines the best?

Stamp census reports show how the market rewards quality—most of the time

[Update, Aug. 18: I’ve added some amendments and clarifications to the conclusions at the end of this article.]

There’s a lot of nice stuff in the upcoming Schuyler Rumsey auctions being held Aug. 25-28 at the Great American Stamp Show in Sacramento. Today I’ll take a look at just how nice, and the different ways we have to measure “nice.”

One way of judging a stamp is simply to look at how much it sold for previously. Such data is often a valid yardstick, based on the assumption that knowledgeable collectors will judge a stamp fairly and be willing to pay appropriately for better quality.

Another way is to try and objectively measure the attributes of a given stamp, using standard metrics based on the centering of the design within the stamp’s edges, its soundness, freshness and overall “eye appeal.” This is often referred to as grading.

But do these two criteria—price and grade—always sync up? Any professional philatelist will tell you that, despite their best efforts to leverage their decades of experience to give accurate pre-sale estimates, auction results can be fickle. There are plenty of examples each week where a given stamp or cover dramatically over-achieves or under-achieves expectations based on its quality or grade.

And therein lies a good part of the sport of buying stamps at auction.

To study this correlation, let’s examine the data behind a couple of items in the Rumsey sale of the Peter Iwate collection of better United States stamps. Specifically, the exceptional example of the 1851-56 1¢ stamp, type III, catalogued as U.S. Scott 8.

[For those who are new to this, a super-quick primer into this relatively advanced area—

The 1851-56 1¢ stamp was printed by the firm of Toppan, Carpenter, Casilear & Co. using four printing plates, each of 200 stamps divided into left and right panes of 100. The first plate was refurbished, so it is known in two “states,” early and late, making a total of five plates from a philatelic perspective.

Unfortunately, the design of the stamp was a little bit too tall for the space available on the plates and had to be crowded in, so in most cases, a little bit of the top and/or bottom of the ornate scroll design is missing. Also, over time the plates wore out as more of the design disappeared due to the erosive action of the ink and paper. Philatelists categorize the stamps by how complete or incomplete these top and bottom frames are, and whether they were retouched when too much went missing. They are grouped by type, from I to V. Individual stamps are also referred to by their plate position, whether they come from the left or right pane, the number of the plate and (if applicable) whether it is the Early or Late (refurbished) state:

Type I stamps have the complete, original design at top and bottom (listed as Scott 5). Actually, only one single position on one plate (7R1E) has this characteristic, making it literally a one-in-a-thousand variety—a rare and sought-after stamp;

Types Ia, Ib and Ic (Scott 6, 5A and 6b respectively) show part(s) of the complete frame at top and/or bottom;

Type II (Scott 7) shows the complete top but a total lack of the bottom frame;

Types III and IIIa (Scott 8 and 8A) show not only missing scrolls and balls from top and/or bottom frames but also a broken or missing outline to the labels “U.S. Postage” and “One Cent”—the bigger the breaks in the outline, the more desirable;

Type IV (Scott 9) shows some degree of retouching or recutting of the missing parts;

Types V and Va show parts of the sides missing, and belong only to subsequent perforated issues from later plates (Scott 24).

The commonest types are II and IV, which in Scott are valued at $140 and $100, respectively, for very fine used examples showing the characteristics clearly. Type III and IIIa stamps are $1,500 and $800, respectively, for same. The Type I’s are much more expensive.]

Finding a nice Scott 8 (or 8A) means looking out for ample margins at top and bottom, so that the defining characteristics can be clearly seen, especially the all-important missing outlines. Cancels should be unobtrusive and the stamp should be fault-free. Sounds straightforward, but in reality this is a tough ask. Relatively few examples make the cut, and the ones that do tend to be priced accordingly.

The stamp in Rumsey’s lot 3038, shown above, is a dream come true in this regard: boardwalk-sized margins, a light cancel and generally just an OMG-level stamp. It clearly shows missing lines at both top and bottom (making it a type III, rather than the commoner IIIa), and comes with a third-party certificate of authenticity from Professional Stamp Experts that assigns it a numeral grade of 98 (on a scale of 1-100) and a suffix of J (for jumbo). Only a very few other examples exist at the top end of the quality scale, so this is a hugely desirable stamp for the collector obsessed with obtaining the best.

Though a basic example of Scott 8 would be valued in the Scott catalogues at $1,500, the Stamp Market Quarterly, an online price guide published by PSE giving values grade-by-grade, pegs a Scott 8 in 98J at a whopping $32,500—a value supposedly based on past auction results as well as dealer price lists.

The bidding on Rumsey lot 3038 opens at $12,000, not including the eventual 18 percent buyer’s premium the winner will also pay. Is that a fair deal? If you’re thinking about bidding on this stamp, you’ll want to do some homework first, to help you decide what an appropriate bidding maximum would be.

StampAuctionNetwork offers some powerful tools to those who sign up for its Premium Extended Features, including census and provenance highlights for exceptional stamps like this, to help you decide.

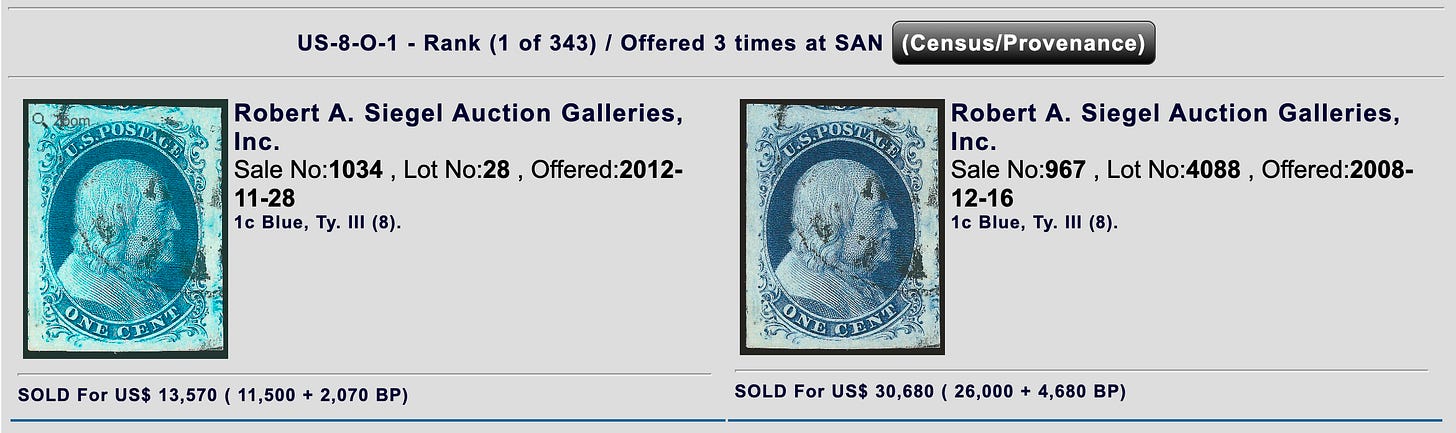

First thing SAN shows me when I look up this lot is the following:

Let’s walk through this screen shot. This same example of Scott 8 has appeared twice before in the SAN database, in past sales by Robert A. Siegel Auction Galleries in New York. It is one of 343 examples of Scott 8 in the database, and SAN thinks it ranks at the very top of that heap, based on its past realizations. But the two realizations shown are pretty far apart: $26,000 (not including buyer’s premium) in 2008 and $11,500 in 2012.

It’s quite unusual for a stamp this nice to drop in price by more than half in just four years, so unless something bad happened to it in the interim, we have to assume one of those results is an outlier. But which one?

First, I click on that black “Census/Provenance” button. It brings up a long page of all the nice Scott 8’s, ranked by average price realized. Some are nicer than others, and several of them have multiple sale records. Prices are all over the place, though a majority fall in the $10,000 to $15,000 range, with a few above and below.

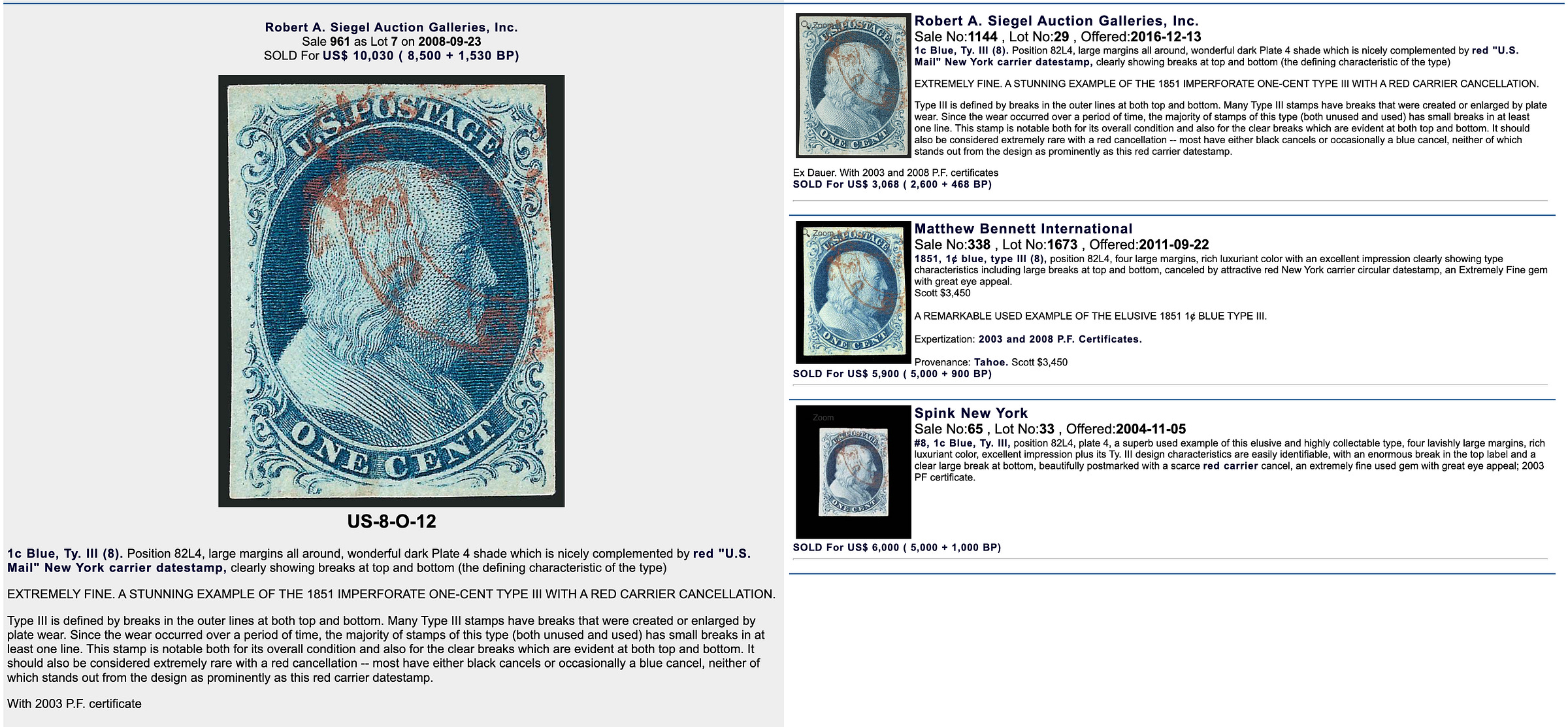

Scrolling down to, say, number 12 in the census, we find this example with prior sales from three different auction houses, along with their descriptions at the time:

Now, this is a splendid stamp, but it is obviously secondary to the one in the current Rumsey sale. It has smaller margins, and the bottom frame break is narrower. Its sales history (without BP) is as follows:

Spink NY, 2004: $5,000;

Siegel, 2008: $8,500;

Bennett, 2011: $5,000;

Siegel, 2016: $2,600

Here, too, we have some pretty big fluctuations over the last two decades. The presence of three different auction firms in the list presumably dispels any notion of a “house effect” on prices, and indeed, the widest variance is within Siegel’s results.

I’d be leery of reading too much into these fluctuations (the usual caveats about bidders’ fickleness apply)—except to draw some very broad conclusions: yes, there was a bit of a stamp-market bubble for so-called “condition rarities” in the late 2000s; yes, what goes up can also come down; and yes, it pays to have done your homework so you can spot the relative bargains when they come along. Wouldn’t you love to be the smart collector who snapped up this bargain in 2016?

Browsing this kind of data, helpfully filtered and organized, is the best way to develop your own sense of what the market consists of and how much comparable stamps sell for. Each stamp is unique, but given enough study, you can develop a gut sense of what an appropriate bid would be. And in the process, you’ll likely find some examples that may be undervalued—their apparent quality outstrips their asking price. Such perceived gaps present opportunities for the smart bidder.

SAN offers additional tools that allow a user to drill down into the database with a fine degree of granularity, tweaking the comparisons between stamps and organizing the results according to various criteria. A lot of it is more geeky and complex than I can get into in this newsletter, but if readers are interested, they should sign up for Extended Features and reach out to Tom Droege, the mastermind behind SAN, who will be happy to provide a demonstration.

Beyond the information at SAN, there are other places to look for previous pricing data. Siegel’s own website is a good one. Their PowerSearch feature brings up four examples of Scott 8 graded 98 or 98J by PSE, with prices realized ranging from $10,500 to $15,500, plus the $26,000 result mentioned earlier.

The non-profit Philatelic Foundation in New York allows visitors to search their database of certificates, many of which include a grade, though not prices. PSE shares population reports of all the stamps they’ve graded, including Scott 8; the PF shows additional examples beyond the PSE census.

While it’s tempting to conclude, as I did initially, that the $26,000 figure from the 2008 Siegel sale seems like an outlier, the market today could also determine that it’s a perfectly fair price—or even a bit low considering our research shows it to be one of the very finest examples out there. The SMQ value for this grade, after all, is $32,500.

Of course, we don’t have any way of knowing what the competition will be like on the day of the sale—that’s what makes auctions such a fun spectator sport!

Til tomorrow,

The “something bad” that happened between 2008 and 2012 was the Great Crash of the Graded Stamp Market. To explain the realization difference between 2008, $26,000, and 2012, $11,500, 2008 was the peak of The Graded Stamp Market Bubble, 2005-2008. 2012-2016 was the nadir of The Great Graded Stamp Depression (mid-2010 to 2017). Since 2018, the GSM has been trending smartly upward. Some issues have appreciated at a blistering pace, while others have moped along. Having said that, at the end of the day, all will depend on whether two or more well-heeled collectors who are into graded stamps want this item. If two or more show up, it will go for a lot. If only one shows up, it will go for one advance over the price the leading graded stamp dealers are willing to pay. They know the market very, very well. Whether you want to join a bidding war is a highly personal choice. I’ve observed, however, that, contrary to the widely-held belief that the stamp market is recession-proof, the very high end of the Graded Stamp Market experiences volatility, and is at least significantly correlated to the movements of the financial markets and the economy.

Another factor one must consider is the trend of issues. Are the 1c Blue imperfs trending up or down. You be the judge.

A final factor is Eye Appeal. While this stamp is fabulous in many ways, and is a “Top of the Pop.” example, this stamp is not God’s gift to Eye Appeal in everyone’s book, due to the cancel and its interplay with the stamp design. There needs to be two or more collectors who care more about the stamp’s many attributes and shrug off, or disagree with, concerns about the weird economic times and lack of universal Eye Appeal— and they need to be players in this auction at this time.